Check out AIGA’s Design Journey’s article on early Winnebago (Ho-chunk) graphic designer, illustrator, and educator Angel De Cora, which I wrote: http://www.aiga.org/diversity-inclusion-design-journeys-essay-angel-decora

The full, final version of the article, which AIGA opted to not post, appears as below, with footnotes included:

Angel De Cora

by Neebinnaukzhik Southall

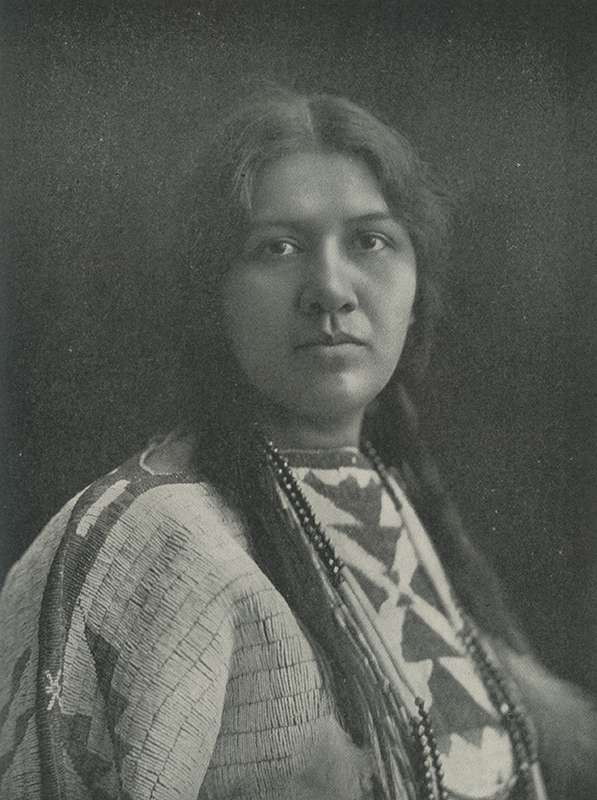

Angel De Cora was an artist, illustrator, graphic designer, and educator, born in a wigwam in Nebraska on the Winnebago Indian reservation in approximately 1868.(i) She was of Winnebago (Ho-Chunk) and French Canadian heritage on both sides of her family, the granddaughter of Winnebago chief Little Decora and the great-grand-daughter of chief Old Grey-Headed Decorah (White War Eagle) on her father’s side.(ii) Her Winnebago name was Hinook-Mahiwi-Kalinaka (Fleecy Cloud Floating in Space), and she was a member of the Thunderbird clan.

In 1883, Angel was kidnapped from her family and taken thousands of miles away to the Hampton Institute in Virginia, which had instated a boarding school for Native Americans.(iii) As official United States government policy, Indian boarding schools were created to “civilize” Native American children, with the goal of stripping them of their cultures, severing their family and tribal connections, and assimilating them into Euro-American society. These schools were often rampant with abuse. Richard Henry Pratt, the founder of the first off-reservation boarding school, the Carlisle Indian School, is infamous for his guiding principle, “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” Despite being educated to devalue Indigenous cultures, Angel De Cora created sympathetic, humanizing depictions of Native peoples throughout her life’s work and advocated for the value and respect of Native American art and design.

At Hampton, Angel De Cora performed well and was generally liked.(iv) After five years, she returned home briefly as part of government regulations, but came back to Hampton in Fall 1888, graduating in 1891.(v) She was then sponsored to attend the Burnham Classical School for Girls in Northampton, Massachusetts.(vi) However, she become uncomfortable with the elitist atmosphere and left the school to attend the School of Art at Smith College in 1892,(vii,viii) also in Northampton, where she was one of their first Native students.(ix) At Smith, she studied under Dwight William Tryon, a well-known tonalist landscape painter.(x, xi) She also worked at the college’s Hillyer Art Gallery, earning her tuition as a custodian.(xii) She received several awards for her work upon her graduation in 1896.(xiii)

After Smith, she was admitted to the Drexel Institute of Art, Science, and Industry in Philadelphia, in September 1896.(xiv) Here, she studied illustration under the famous American illustrator Howard Pyle, who produced many well-known illustrators(xv) and considered her a genius.(xvi) In 1897, the summer after her first year, Angel went to Fort Berthold, North Dakota, following Pyle’s encouragement to paint and draw Native people.(xvii) The following summer, she attended a special course of his as the recipient of a competitive scholarship.(xviii) Due to his connections, she wrote and illustrated two stories for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, “The Sick Child” in the February 1899 issue, and “Grey Wolf’s Daughter” in the November 1899 issue, both featuring Native American girls as the protagonists.(xix)

In 1899, she briefly studied at the Cowles Art School in Boston with Joseph DeCamp, then attended the Boston Museum of Fine Arts School in February 1900, studying under Frank Benson and Edmund C. Tarbell, where she “was awarded an honorable mention in the Concours Scholarships for 1900 and 1901.”(xx)

In her short autobiography, Angel discusses her transition from fine art to commercial art, beginning at the Drexel Institute; she also expressed her belief in the in-born creative talent of Native people (xxi):

While at this Institute I used to hear a great deal of discussion among the students, and instructors as well, on the sentiments of “Commercial” art and “Art for art’s sake.” I was swayed back and forth by the conflicting views, and finally I left Philadelphia and went to Boston. I had heard of Joseph DeCamp as a great teacher, so I entered the Cowles Art School, where he was the instructor in life drawing. Within a year, however, he gave up his teaching there but he recommended me to the Museum of Fine Arts in the same city, where Frank Benson and Edmund C. Tarbell are instructors, and for two years I studied with them.

I opened a studio in Boston and did some illustrative work for Small & Maynard Company, and for Ginn & Company. I also did some designing although while in art schools I had never taken any special interest in that branch of art. Perhaps it was well that I had not over studied the prescribed methods of European decoration, for then my aboriginal qualities could never have asserted themselves.

I left Boston and went to New York City, and while I did some illustrating, portrait and landscape work, I found designing a more lucrative branch of art.

Although at times I yearn to express myself in landscape art, I feel that designing is the best channel in which to convey the native qualities of the Indian’s decorative talent.

As a commercial artist, Angel was involved with a number of book projects. She worked on Old Indian Legends, first published in 1901 by Ginn & Company, featuring Dakota stories retold by her friend Zitkala-Ša (Gertrude Simmons Bonnin), a Yankton writer, musician, and activist. Angel produced a cover design reminiscent of Plains beaded blanket strips, and she painted many illustrations to accompany the stories. Angel designed the cover The Middle Five: Indian Boys at School, published by Small, Maynard & Company in 1901. The author was Francis LaFlesche, who was of Omaha, Ponca and French heritage; the son of Omaha chief Joseph LaFlesche; and the first Native American ethnologist. The book captured his time at a mission school. The cover features a stylized scene of two tipis, with a bow and several arrows as border motifs. Angel also produced an illustration for the frontispiece, an emotionally charged painting depicting a Native American boy in a school uniform comforting another boy, a recent arrival in Native dress, who covers his face while he weeps. For Mary Catherine Judd’s book Wigwam Stories Told by North American Indians, published in 1904 by Ginn & Company, she designed the cover and the title page, and produced a number of illustrations as well as a plethora of charming initial letters, many of which conceptually match the stories.

Angel produced a number of designs for The Indian’s Book, published in 1907 by Harper and Brothers Publishers, which features a collection of songs and stories from diverse Native American ethnic groups across the continent, gathered by Natalie Curtis. The book received national attention, and included an introductory note from president Theodore Roosevelt. Angel designed the main title page with stylized eagles as a way to collectively represent the broad content of the book, the concept of which is described in the book:

The title-page, by Angel De Cora, (Hinook Mahiwi Kilinaka), has for the motive of its design an adaption of an old Indian design which represents in highly conventionalized form the Eagle, and the Eagle’s Song. The soaring eagle is seen in the grey figure whose points are the two out-spread wings, with the tail in the centre. The paler spot at the top of the figure is the eagle’s head; from the beak rises the song – waving lines which broaden out as the song floats on the air. The whole symbol is used in decorative form throughout the page, two eagles being joined together by the tips of wings and tails to form a symmetrical design. In the centre of the page, at the top and bottom, and at the sides, is seen the eagle-symbol, while the page is framed, as it were, in the symbol of the song.

The eagle is loved and revered by the Indians. He is the strongest of all birds. He soars aloft, and he may look upon the sun, the giver of life, the celestial emblem of divine force. Therefore has the symbol of the Eagle and the Eagle’s Song been chosen for the title-page of “The Indians’ Book.”

Angel also created lettering and borders for the title pages of the book, which complemented the drawings of other contributing Native artists and referenced the diverse design conventions of their respective tribes. At the time, the publishers had not seen this sort of inspired lettering before.(xxii) She also presumably designed the cover, which clearly draws from the abstract, geometric designs created on parfleche bags by Plains Indians.

In 1906, she was offered a position to teach Native American art at the Carlisle Indian School by Francis E. Leupp, Commissioner of Indian Affairs.(xxiii) This appointment represented a major policy shift for the institution.(xxiv,xxv) At Carlisle, she developed a program to teach the students characteristic designs from a variety of North American Indigenous cultures. An important function of her program was to build the self-esteem of the students and instill pride in their heritage.(xxvi)

Angel frequently traveled, giving talks and presenting papers at conferences on Native American art and design. The Arts and Crafts movement gave Angel a vehicle to promote the value of Native American art and design, as she expressed in her speech for the Twenty-fifth Annual Meeting of the Lake Mohonk Conference of Friends of the Indian and other Dependent Peoples in 1907:

The art department of Carlisle has taken a departure from the regular routine work of public schools. We do not study any of the European classics in art. We take the old symbolic figures and forms which we find on beadwork, pottery, and baskets for the basis of our study. We are familiarizing ourselves with the different styles and methods; then we create designs according to these old established methods and apply them to the products of the workshops of the school in such ways as wood-carving, printer’s borders, metal work, wall decoration, weaving and needlework.

There is a general revival throughout the country of the old handicrafts and skilled hands are in demand. Let me tell you that the Indian is an apt pupil for any sort of handicraft. The basket and textile weavers, pottery and metal workers are already well established. Each of these industries can be expanded in various directions both for utility and ornament. The simple dignity of Indian design lends itself well to ways of conventional art and I think the day has come when the American people must pause and give recognition to another phase of the Indian’s nature which is his art.(xxvii)

Angel was a member of the Society of American Indians, one of the first Native-led Native American rights organizations, and she also designed a logo for the Society.(xxviii) At the First Annual Conference of the Society of American Indians in 1912, she gave a presentation, “Native Indian Art,” speaking of Native peoples collectively, which included her aesthetic philosophies, the value of Native American designs as equal to any other tradition, the design characteristics of various tribes, discussion of her work with students at Carlisle, and the potential for wide commercial application of these designs:

The nature of Indian art is formed on a purely conventional and geometric basis, and our endeavors at the Carlisle Indian School have been to treat it as a conventional system of designing.… By this development all the page ornamentations of the Carlisle school magazine, the Red Man, were made by the pupils. We have made stencil designs for the friezes and draperies, designs for rugs, embroideries, applique, wood carving, tiles, and metal work. We not only have produced the designs, but they have been applied whenever we had the material at hand. Rugs, draperies, sofa cushion covers and smaller articles were designed and made by the girls of the Art Department and the boys of the Art Department under Mr. Dietz, who is also a trained artist, have done all the pen and ink decorations for the Red Man, such as the page borders, initial letters and other page ornaments. In the metal work Indian designs were wrought in silver jewelry, copper and brass trays in all the novelty shapes.

The Indian designs modified and applied to interior house decoration are especially in harmony with the so-called “mission” style, the geometric designs lend themselves well to the simple and straight lines of mission furniture.… By careful study and close application many hundred designs have been evolved. Many of these designs have been thrown upon the market of the country and each one has brought its financial reward, but more than that, from these small and unassuming ventures, we have drawn the attention of artists and manufacturers to the fact that the Indian of North America possessed a distinctive art which promises to be of great value in a country which heretofore has been obliged to draw its models from the countries of the eastern hemisphere.… Manufacturers are now employing Indian designs in deteriorated forms. If this system of decoration was better understood by the designers, how much more popular their products would be in the general market.

An Indian with the technical training of a good art school would readily find employment with establishments that employ designers.… As all peoples have treasured the history of their wanderings in some form, so has the American Indian had his pictograph and symbolic records, and with the progress of time he has evolved it into a system of designing, drawing his inspiration from the whole breadth of his native land.

Angel participated in several exhibitions throughout the years, including the 1901 Buffalo Pan-American Exhibition (for which she produced designs for furniture), the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904, and the Jamestown Tercentennial in 1907, which showed her student’s work.(xxx,xxxi)

At the end of December 1907 in New Jersey, Angel married the younger William Henry “Lone Star” Dietz, a student at Carlisle who presented himself as a Native American.(xxxii) He became her assistant at the school soon after.(xxxiii) Together, they collaborated on a number of projects. They illustrated Yellow Star: A Story of East and West, published in 1911 by Little, Brown, and Company and written by Elaine Goodale Eastman, the wife of Dr. Charles Eastman (Ohíye S’a), a Santee-Sioux physician. They also collaborated on The Little Buffalo Robe, written by Ruth Everett Beck and published in 1911. Dietz became involved with the school’s publications, including The Indian Craftsman, later renamed The Red Man, which was launched February 1909.(xxxiv) Notably, this publication was printed by Native students, and many of the designs and illustrations in the magazine were produced by students in Angel’s program. While Dietz illustrated the bulk of the covers, Angel created the September 1913 cover illustration of The Red Man (Vol 6., No. 1), entitled “Indian Nurse.” She also modeled for a photograph which her husband used in his cover illustration of the November 1912 issue of The Red Man (Vol. 5, No. 3). (xxxv)

Following the dissolution of the Indian art department and an investigation that engulfed the school, Angel left Carlisle in 1915 to further pursue her career as an artist. In 1918, she and Dietz divorced.(xxxvii) The same year, she illustrated Devonian fauna for the New York State Museum.(xxxviii) While Angel had artistic ambitions yet, she became ill and died of pneumonia and influenza in February 1919.

In the Summer 1919 issue (Vol. 7, No. 2) of The American Indian Magazine, produced by the Society of American Indians, her friend Zitkala-Ša, the editor, recognized Angel for her gift of $3,000 to the Society of American Indians in her will and expressed gratitude: “Angel DeCora Dietz, living and dying, has left us a noble example of devotion to our people. Let us take heed. Let us prove our worth even as she has done.”(xxxix) The same issue features illustrations of Angel’s accompanying an article written by Dr. Charles Eastman, “The American Eagle: An Indian Symbol,” discussing the significance and symbology of the eagle and its feathers, a subject which is just as timely today, in the light of the still-present issue of cultural appropriation. The illustrations include a number of eagle feathers and a full-page portrait of a Native man wearing a headdress.

Following her death, a number of eulogies recognized Angel and her work. Throughout her career, Angel was frequently mentioned in the press, though unfortunately, as the result of being a Native woman, she was often romanticized and stereotyped. Though forgotten for many years, Angel De Cora is now receiving the serious attention and discussion she deserves. As scholar Yvonne N. Tiger concludes in her master’s thesis, Angel de Cora: Her Career as an Art Instructor and Her Racialized Perspectives While Employed at Carlisle, 1906-1915:

De Cora left behind a wonderful legacy for Indian people. In her art, one can see the difficult path that she walked; De Cora had both feet and mind firmly planted in the white world, while her heart struggled with what it meant to be an Indian. This struggle played itself out in her ideas on teaching Indian art. Her art and illustrations are an important part of Indian and art history.” In one of her speeches, Angel de Cora said, “There is no reason why the Indian workman should not have his own artistic mark on what he produces.” As an assimilated Indian artist and educator, De Cora left her indelible mark on her work. Her pioneering efforts resulted in the implementation of art programs in Indian boarding schools across the country, and, many years later, led to a renaissance in Indian art. Angel de Cora was responsible for the earliest efforts geared towards the preservation of Indian art.(xxxx)

Indeed, a hundred years later, much of her work and intellectual explorations are relevant to graphic designers today.

Recommended Reading:

- Fire Light: The Life of Angel De Cora, Winnebago artist, by Linda M. Waggoner

- “Angel DeCora’s Cultural Politics,” The Indian Craze: Primitivism, Modernism, and Transculturation in American Art, 1890-1915, by Elizabeth Hutchinson

- “Angel DeCora: American Artist and Educator” by Sarah McAnulty, in Nebraska History Volume 57, No. 2 (Summer 1976), pp. 143-199.

- American Indian Artist Angel DeCora: Aesthetics, Power, and Transcultural Pedagogy in the Progressive Era, by Suzanne Alene Shope, (2009). Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers. Paper 113.

- Angel de Cora: her assimilation, philosophies, and career as an art instructor while employed at Carlisle, 1906-1915 (Unpublished master’s thesis) by Yvonne N. Tiger (2008), University of Oklahoma, Bizzell Memorial Library, Peggy V. Helmerich Reading Room.

FOOTNOTES:

i) Linda M. Waggoner, Fire Light: The Life of Angel De Cora, Winnebago Artist (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008), 3

ii) Ibid., 3-6.

iii) Ibid., 24-27.

iv) Ibid., 30.

v) Sarah McAnulty, “Angel de Cora: American Indian Artist and Educator,” Nebraska History 57, no. 2 (1976): 143-199. Accessed at http://www.tfaoi.org/aa/4aa/4aa27.htm

vi) Ibid

vii) Linda M. Waggoner, Fire Light, 58-58.

viii) Sarah McAnulty, “Angel de Cora.”

ix) Linda M. Waggoner, Fire Light, 68.

x) Sarah McAnulty, “Angel de Cora.”

xi) Linda M. Waggoner, Fire Light, 60-62.

xii) Ibid., 59.

xiii) Ibid., 68.

xiv) Ibid., 69-70.

xv) Ibid., 69.

xvi) Ibid., 79.

xvii) Sarah McAnulty, “Angel de Cora.”

xviii) Linda M. Waggoner, M. Fire Light, 76.

xix) Ibid., 75-82.

xx) Sarah McAnulty, “Angel de Cora.”

xxi) Angel DeCora, “Angel DeCora – An Autobiography,” The Red Man, March 1911, 280-285.

xxii) Linda M. Waggoner, Fire Light, 129.

xxiii) Angel DeCora, “Angel DeCora – An Autobiography.”

xxiv) Linda M. Waggoner, Fire Light, 132-133.

xxv) Elizabeth Hutchinson, The Indian Craze. Primitivism, Modernism, and the Transculturation in American Art (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 202-203.

xxvi) Ibid., 203-204.

xxvii) Proceedings of the Twenty-fifth Annual Meeting of the Lake Mohonk Conference of Friends of the Indian and other Dependent Peoples, Lake Mohonk Conference, 1907, 16-18

xxviii) Linda M. Waggoner, Fire Light, 194-195.

xxix) Angel DeCora, “Native Indian Art,” Report of the Executive on the Proceedings of the First Annual Conference of the Society of American Indians Held at the University of Ohio, Columbus, Ohio – October 12-17, 1911, I (Washington, D.C.: Society of American Indians, 1912), 85-87.

xxx) Elizabeth Hutchinson, The Indian Craze, 200-202.

xxxi) Sarah McAnulty, “Angel de Cora.”

xxxii) Linda M. Waggoner, Fire Light, 153-154.

xxxiii) Ibid., 159.

xxxiv) Ibid., 164-175.

xxxv) Tom Benjey, Keep A-goin’: The Life of Lone Star Dietz (Carlisle, PA: Tuxedo Press, 2006), 72-75

xxxvi) Linda M. Waggoner, Fire Light, 210-236.

xxxvii) Sarah McAnulty, “Angel de Cora.”

xxxviii) Ibid.

xxxix) Society of American Indians. The American Indian Magazine. (Washington, D.C.: Society of American Indians, 1919), 62

xxxx) Yvonne N. Tiger, (2008). Angel de Cora: her assimilation, philosophies, and career as an art instructor while employed at Carlisle, 1906-1915 (Unpublished master’s thesis), 30. University of Oklahoma, Bizzell Memorial Library, Peggy V. Helmerich Reading Room.