My article, Exploring Native Design: The Making of a Designer: Mark Rutledge is a biography of the Yukon-based Ojibwe designer Mark Rutledge, appearing in the Fall 2014, issue 4 of First American Art Magazine.

The Making of a Designer: Mark Rutledge

by Neebinnaukzhik Southall

As appears in First American Art Magazine

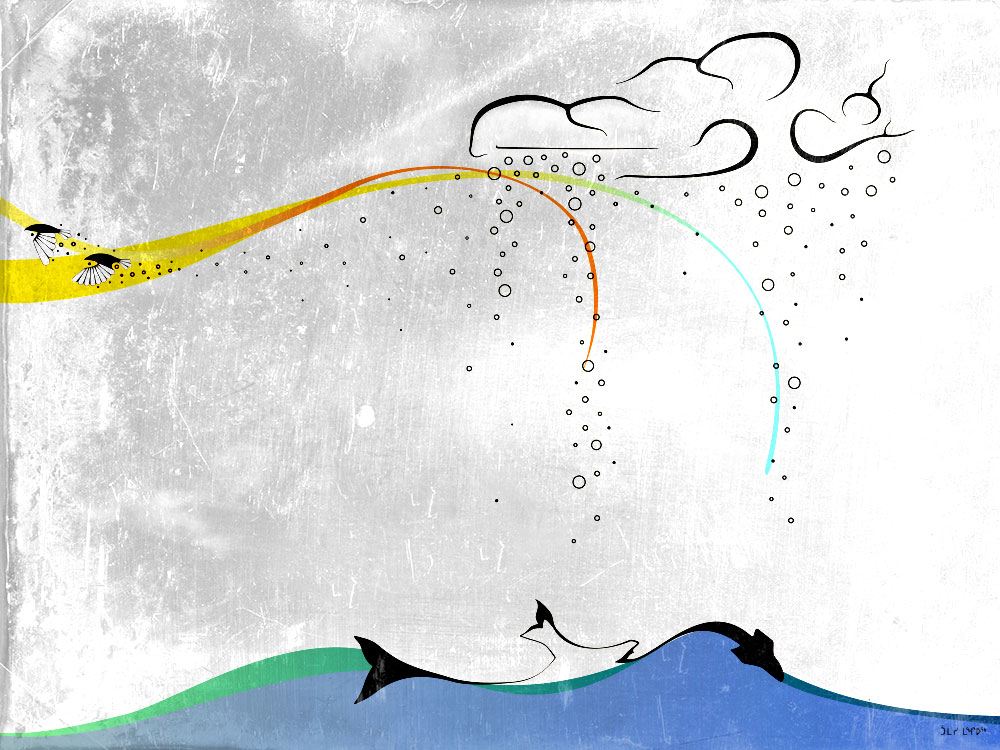

MARK RUTLEDGE, A PROUD OJIBWE from the Little Grand Rapids First Nation in Manitoba, Canada, has worked in the design industry for over 15 years. He has designed for the Canadian government, NGOs/non-profits, Fortune 500 companies, the technology industry, Yukon tourism, and Native clients, including the Chiefs of Ontario, SPIRIT Magazine, and the Canadian Aboriginal Music Awards. He is an accredited member of the Society of Graphic Designers of Canada (GDC) and recently became the president of the GDC’s Arctic Chapter. He works at Outside the Cube in Whitehorse, Yukon, where he lives with his wife Tracy—a fellow designer he met in college—and their three children. Mark’s successful career results from an adventurous and at times tumultuous journey.

As a child Mark was caught in the “Sixties Scoop,” a tragic period extending from the 1960s to the 1980s in which the Canadian government stole thousands of Native children from their communities. The start of his life was brutal—at an abusive group foster home.

“We’re survivors,” asserts Mark. “We’re still here.”

Like many other Native children, Mark was adopted and raised by a white couple. Fortunately, these new parents were open-minded and never tried to hide his heritage or keep him from finding his Native family.

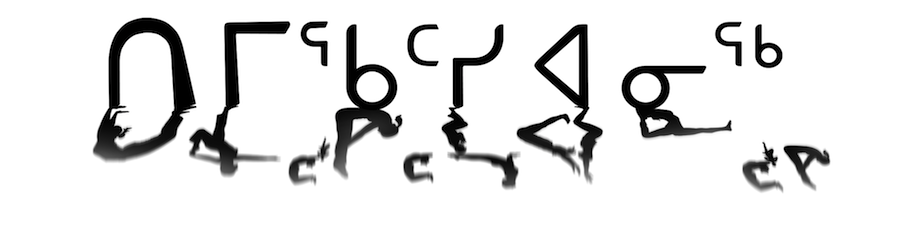

His adoptive family also nurtured his creativity, which he exhibited early on. When he was six or seven years old—while other children built snowmen—Mark built letterforms in the snow to form a statement. “I didn’t know it was typography,” he says of his early fascination. His first design course came in sixth grade. His mother, a schoolteacher, enrolled him in a night course for high schoolers. Surrounded by teenagers, Mark learned about commercial art, sign making, and lettering in particular.

After completing high school, Mark dreamed of going to the Ontario College of Art and Design in Toronto. However, his guidance counselor told him he wasn’t good enough, and besides, art wasn’t a real career. As a result, Mark enrolled in Seneca College in Toronto, where he studied computer science and spent his first year programming. It wasn’t a good fit, and he performed poorly. It took him a week to muster up the courage to tell his dad he was failing. Rather than being angry, his dad suggested Mark take graphic design instead. Seneca College was actually one of the first programs in the area to offer a degree in design. Mark enrolled the next year, and his computer experience proved to beneficial. “I had an edge on the other kids because I knew how a computer worked,” explains Mark. While admitting he wasn’t good at something was difficult, he sees failure as a necessary step to improvement. “Everyone fails. How are you supposed to become successful if you don’t fail?”

When Mark first went to school, graphic design involved paste-ups (an arrangement of physically placed illustrations and text on paper), blue-lines (proofs printed in shades of blue), and film for printing. When the industry shifted, Mark went back to school to further immerse himself in digital, online, and interactive media. “You have to evolve with the field,” stresses Mark, and maintain a thirst for knowledge. “If you don’t know the tools, how else are you supposed to be a designer?” A solid foundation in the history of the field and knowledge of its influential designers is also vital.

He is inspired by great graphic designers, such as Massimo Vignelli, a renowned designer who sadly recently passed away. Mark had the fortune to meet him at a conference and loves his clean, modernist style. Also among his favorite designers are Victor Pascual (Navajo-Mayan), Ryan Red Corn (Osage), Dwayne Bird (Peguis First Nation), and Louie Gong (Nooksack), in how they utilize Native iconography with flair in their work.

Mark’s first design job out of school was at Aboriginal Voices, an early Native lifestyle magazine published by Cayuga actor Gary Farmer. As their only designer, for a year or two he laid out the magazine late into the night in a “swanky office” in an old building on Queen Street in the fashion district in the core of downtown Toronto. The location was happening and work atmosphere exciting. “I met all these famous Indians,” enthuses Mark, such as Cree musician Buffy Sainte-Marie, as well as many Native actors.

Rumors spread that the magazine was folding, so Mark started job-hunting and received two offers—a fashion magazine and the student administration at Ryerson University. Despite loving fashion, he chose the latter. At Ryerson, he mingled with other young people, designed diverse communication material, and was in the hub of downtown Toronto.

Over time, Mark didn’t feel challenged enough, so in 1998 he sought work at a design studio to sharpen his skills. The studio, Hangar 13 Art & Design, was in Ottawa, Ontario. Back in “another old warehouse building,” he primarily designed for government agencies. He worked with a team of designers, and his setup was cutting-edge—working a Mac computer with two huge monitors for the first time. “I wanted to work at a boutique design studio, and here I am!” he thought.

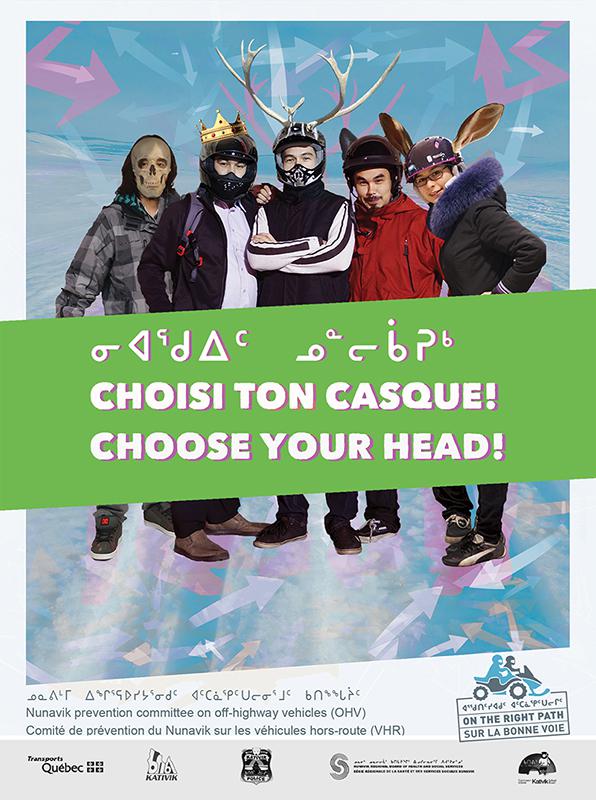

First Nations client work poured in as people realized that he was a Native designer. The husband-and-wife team that ran Hangar 13 and Mark formed the Thunderbird Group, a sister company to serve Native clients. Mark developed branding inspired by WWI and WWII Indigenous fighter pilots to fit Hangar 13’s aircraft-influenced branding. The couple was very open to working with Indigenous people, stemming from their experiences growing up in small communities, living on reserve, and having Native friends. Mark’s time working with them was a mutually beneficial and educational relationship. “There is a way for us to understand each other in a good way,” asserts Mark, regarding Indigenous and non-Indigenous interactions.

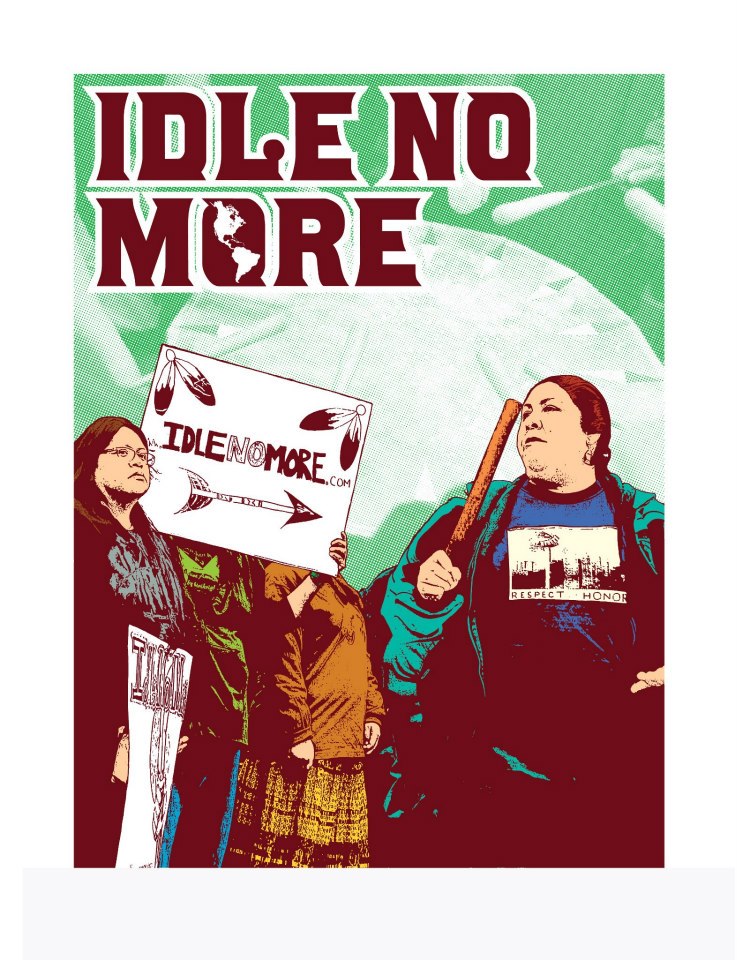

The Thunderbird Group hired Native consultants, including writers, photographers, historians, and elders, and sought to “change the perception of what Native people are. We’re professionals,” says Mark. The Thunderbird Group was a bridge between people—not only designing but also educating. Mark taught corporations wanting to tap the Native market that they couldn’t just “throw money at the people.” He showed clients how to best approach communities and stressed the importance of respect. In that vein, he hates when “non-Indigenous companies try to latch on for profit only, not community,” when interacting with Native groups. A percentage should go back to the community, and the relationship should be positive.

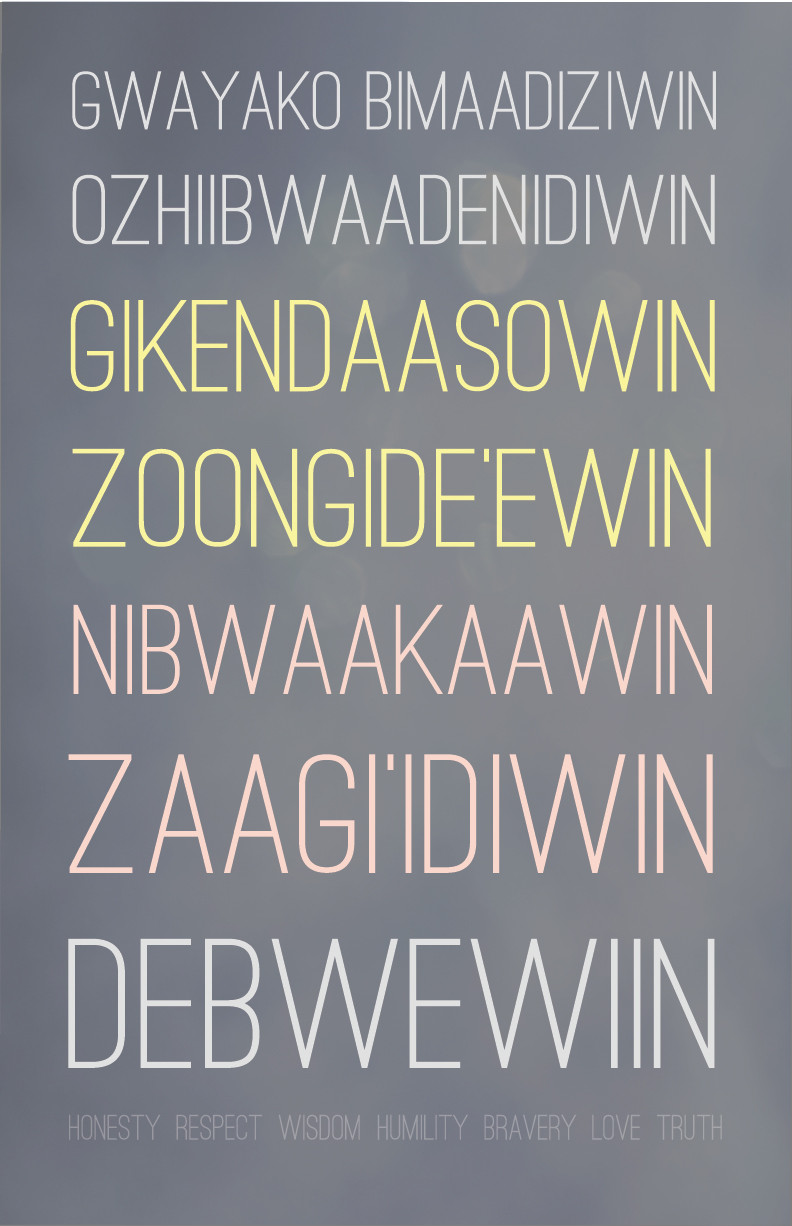

While Mark is honored that people approach him due to his diverse background and skill set, clients should not expect the stereotypical. Clients have requested feathers, dreamcatchers, sweetgrass, and the four directions. There are other icons and concepts. “There’s more to communication than the first idea,” says Mark, stressing the need to dig deeper. “I do a lot of research,” says Mark. “I don’t know everything about every culture.” He admits he was surprised to learn how many First Nations were in British Columbia alone. “We want to make you stand out from the rest of your competition,” says Mark, and that is why a nuanced concept is vital.

When Mark first started working as a designer, he focused on winning awards. Now it’s simply about “doing good design for great clients and having fun while doing it.” And giving back to the community. He provides workshops on communication, focused on giving remote artists the understanding of what it takes to reach an online market.

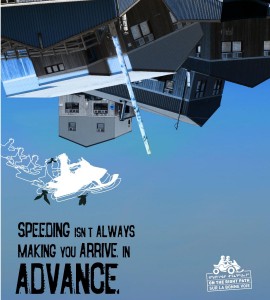

His lifestyle has shifted as well. Mark relates his experience working at several big agencies; driven by money, the designers were locked in the studio, working around the clock. At his current job at Outside the Cube in Yukon, there’s a stark difference in outlook. The owner of the company worked at a large agency herself and sees no need for driving people to an early grave. Here the employees are surrounded by wilderness, a beautiful landscape of mountains and lakes. Work, play, and family life are balanced, and Mark walks the trails with his family.

His children are heavily into technology and are beginning to appreciate what he does. His oldest son now understands what a designer is. To foster their creativity, he provides his children with watercolors, markers, and crayons and brings home printouts of his work that they can draw over. He encourages them to not compare themselves to other artists and tells them, “You’re being creative, and that’s what counts.”